Advancing Precision Medicine: Genomics, Metabolomics, and Clinical Trials

Monday, October 12 was the evening of an interesting talk at BIOCOM. Teresa Gallagher, founder of the San Diego Clinical Research Network (SDCRN) introduced the moderator of the event, Arnold Gelb, MD, Senior Medical Director at Halozyme. Rather than attempt to summarize all of the topics examined, the goal of this blog is to give a sampling of some of the areas discussed during the event.

Deterministic versus probabilistic genetics

The first speaker of the evening was Amalio Telenti, MD, PhD, Head of Genomics at Human Longevity, Inc. His talk touched on the ever-present nature vs. nurture debate. Do our genes determine a particular characteristic or merely influence the probability of developing that characteristic? In the world of whole genome sequencing, this can be described as deterministic versus probabilistic genetics.

In general, a deterministic trait would be something like Tay-Sachs Disease: if you have two copies of the gene for this condition, you have a better than 99% chance of developing the disease. A probabilistic trait is one with many genes that influence it, like height. Outside factors like disease and diet also affect how tall an individual grows. Hence, height is a probabilistic trait.

Telenti predicted that genomics will not revolutionize all aspects of medicine; but some medicine will be revolutionized profoundly; clinical trials will benefit the most. Genomics will be employed to stratify patient populations both before studies are commenced and after all the data is collected. Ideally genomics will be utilized to both determine who benefits from a drug and who should not take the drug.

Metabolomics combines genetics and environment

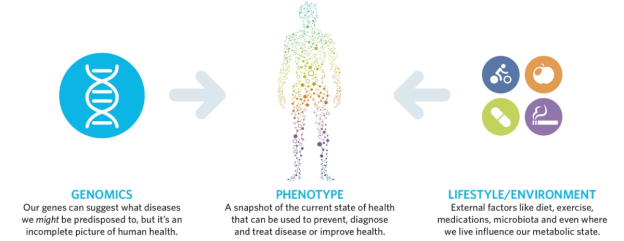

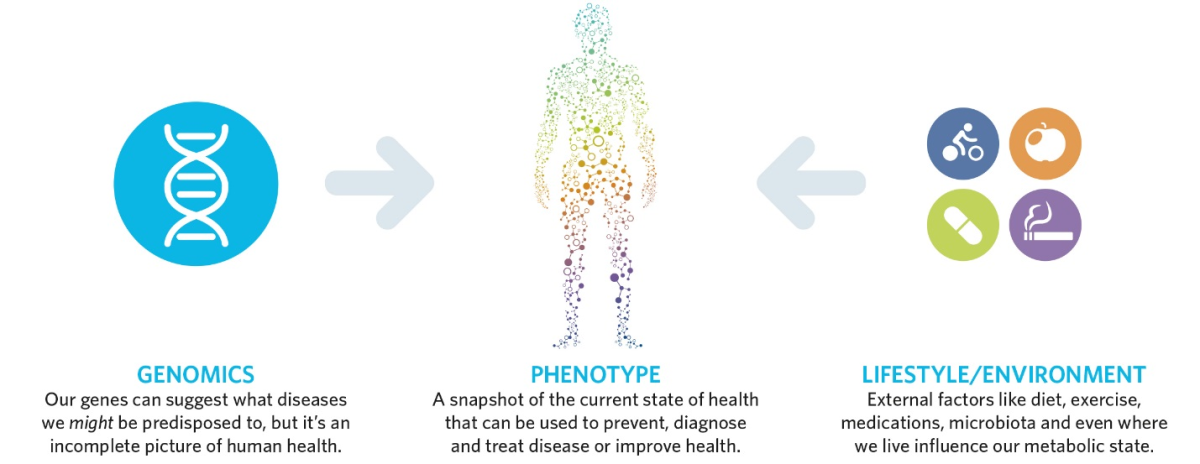

Steve Watkins, PhD, Chief Technology Officer of Metabolon spoke next. Metabolon specializes in metabolomics, offering comprehensive measurements of small molecules such as glucose, cholesterol, cortisol, and amino acids in a CLIA-certified lab.

Metabolites reflect the integration of genetic and environmental influences on an individual. Diseases can be prevented and diagnosed by checking on an individual’s metabolites. Response to disease treatment can be monitored by testing metabolites. Metabolomics is emerging as an effective tool in precision medicine.

Watkins shared that Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences recently published a study led by Baylor University’s Tom Caskey, MD. Caskey comprehensively tested the metbolites of many patients with no frank disease. Metabolon’s platform spotted underlying health issues not previously noticed in the patients’ genetic data.

For example, Patient 3905 had very high levels of sorbitol and fructose, but no clinically significant mutation was reported in their genome. Looking back at the genomic data for that individual, a mutation in the fructose pathway indicating “fructose intolerance” was discovered. This mutation had been overlooked previously. When discussing these results with the patient, the patient simply stated that fruit bothered him, so he refrained from eating it.

In the same study, Patient 3923 carried a gene for Xanthinuria type 1. He showed no symptoms of the disease such as kidney stones, suggesting the gene was not penetrant (or not expressed), leaving the patient symptom-free.

In conclusion, Watkins stated that metabolomics can be used in a number of ways:

1) By identifying pathways of interest for genetic assessment

2) By revealing non-penetrance of genes suspected of being deleterious

3) By enabling monitoring and understanding of metabolic conditions

Which drugs to use in cancer treatment?

The final speaker for the evening was Nicholas Schork, PhD Professor and Director of Human Biology at the J. Craig Venter Institute. He focused on emerging themes of design for precision medicine trials.

Schork presented several novel ideas. One was the idea of vetting algorithms for the treatment of cancers based on the mutations the cancers carry. Some hospitals already use this method, begging the question of who has the best algorithm for cancer treatment. As Schork points out, this has led to some interesting conversations with the FDA. He envisions clinical trials in the future for the evaluation of algorithms for cancer treatment with existing drugs, in direct contrast to the conventional clinical trial, usually designed to assess the effectiveness of a new drug.

In all, this was an exciting presentation of cutting-edge research and future directions in precision medicine.